What is the ACL?

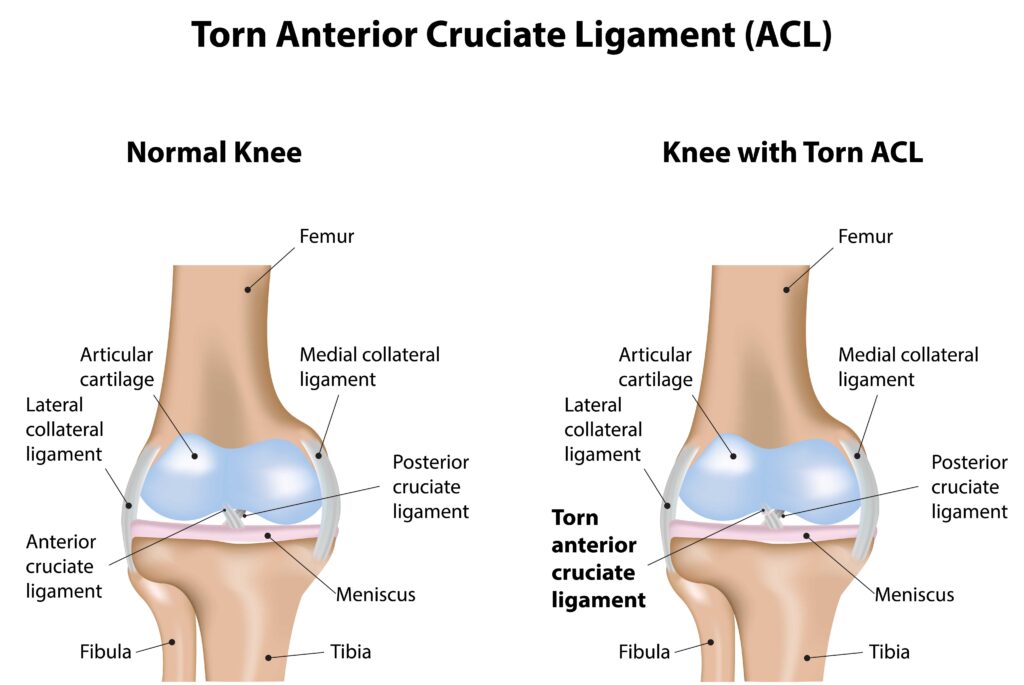

The knee functions as a hinged joint made of the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia (shin bone). The ACL is one of the ligaments within the knee that helps to connect the two bones.

The ACL prevents the tibia from sliding too far forward relative to the femur, but it is also important in rotational stability of the knee. It runs diagonally in the middle of the knee and is one of the most commonly injured ligaments in the knee.

What is an ACL Tear?

An ACL tear occurs when this ligament is stretched or torn, often due to sudden stops or changes in direction, direct blows to the knee, or hyperextension. While ACL tears are most commonly associated with sports injuries, they can also occur during everyday activities or accidents.

Causes of ACL Tears

Several factors can contribute to the likelihood of an ACL tear, including:

- Sports Injuries: High-impact sports like basketball, soccer, football, and skiing frequently involve movements that put stress on the ACL, increasing the risk of tears.

- Improper Landing Techniques: Landing from a jump with poor form or on an uneven surface can lead to ACL injuries.

- Sudden Stops or Changes in Direction: Abrupt changes in movement, such as pivoting or cutting, can place excessive strain on the ACL.

- Weak Muscles or Imbalance: Inadequate strength or imbalances in the muscles surrounding the knee can increase the risk of ACL tears.

Several studies have also shown that female athletes have a higher incidence of ACL injuries than male athletes. The reason for this isn’t entirely known, but proposed theories include differences in bony anatomy, muscle strength, and neuromuscular control.

Sports medicine surgeon, Dr. Matthew Lilley, provides a more in depth explanation on ACL Injuries in this short video.

Examination for ACL Tears

During the physical examination with your sports medicine orthopedic surgeon, we will look for several physical findings. First, the amount of fluid within the knee is assessed. When the ACL is torn, the artery that supplies the ACL tears is torn as well, and the knee gets filled with blood. This fluid can be detected by the exam. Range of motion is usually limited. The outside back of the knee (lateral posterior aspect of the tibia) is tender to the touch and corresponds to the bone contusion (bruise) that usually occurs with this injury.

During a comprehensive examination, your orthopedic surgeon will evaluate the knee for potential injuries beyond the ACL, including meniscus tears. To assess the ACL, they may conduct tests such as the Lachman test and the pivot shift test. The Lachman test involves evaluating the forward motion (translation) of the tibia relative to the femur, comparing results between both knees. Meanwhile, the pivot shift test evaluates rotational stability. Additionally, the examination encompasses testing of other ligaments within the knee to ensure a thorough assessment of its overall integrity.

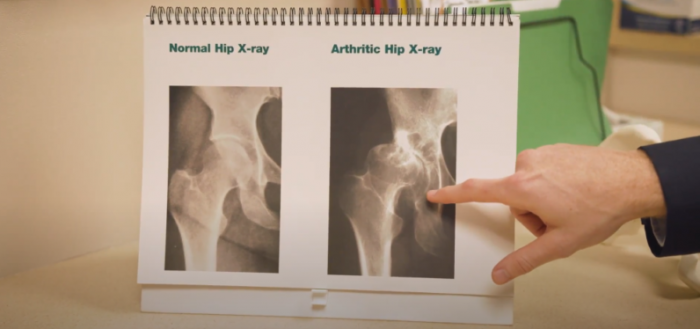

X-rays are commonly used as a preliminary screening tool to rule out fractures. Occasionally, they may reveal a “Segond fracture,” which is a telltale sign of an ACL tear. While history and physical examination alone often suffice for diagnosing an ACL tear, sports medicine orthopedists may opt for an MRI to evaluate any additional injuries associated with ACL tears to refine the treatment plan.

Treatment for ACL Tears

The treatment approach for an ACL tear depends on various factors, including the severity of the injury, the patient’s activity level, and their overall health. While some minor tears may respond well to conservative measures, more severe tears often require surgical intervention. Here are the primary treatment options:

- Conservative Management: For minor tears or patients who are not candidates for surgery, conservative treatment may involve rest, physical therapy, bracing, and activity modification. Physical therapy aims to strengthen the muscles surrounding the knee and improve stability.

- Surgical Reconstruction: For active individuals, athletes, or those with severe tears, surgical reconstruction of the ACL may be recommended. ACL reconstructive surgery involves making a new ligament to take the place of the torn ACL. When the ACL tears, it disrupts the blood supply to the ligament and it is not able to repair itself. During this procedure, the torn ligament is replaced with a graft, typically sourced from the patient’s hamstring tendon, patellar tendon, or a cadaver donor.

Watch professional mountain bike racer, Porsha Murdock’s, amazing comeback after undergoing surgery for her torn meniscus, ruptured ACL, and partial MCL tear.

Post-operative Care for ACL Tears

Recovery from ACL reconstruction surgery is a gradual process that requires patience, dedication, and adherence to the prescribed rehabilitation program. While specific protocols may vary depending on the surgeon and the patient’s individual circumstances, common elements of post-operative care include:

- Immobilization and Protection: Initially, the knee may be immobilized in a brace to protect the surgical site and promote healing. Crutches may also be used to assist with mobility.

- Physical Therapy: Rehabilitation typically begins soon after surgery and focuses on restoring range of motion, strengthening the muscles around the knee, and improving balance and stability.

- Gradual Return to Activity: Athletes should follow a structured return-to-sport program under the guidance of their physical therapist and surgeon, gradually increasing the intensity and complexity of activities to minimize the risk of re-injury.

- Monitoring and Follow-up: Regular follow-up appointments with the orthopedic surgeon are essential to monitor progress, address any concerns, and adjust the rehabilitation program as needed.

Prevention Strategies

While ACL tears are not entirely preventable, certain strategies can help reduce the risk of injury:

- Strength and Conditioning: Regular exercise focusing on strengthening the muscles surrounding the knee, particularly the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes, can help improve stability and reduce the risk of ACL tears.

- Proper Technique: Athletes should receive proper training on landing, cutting, and pivoting techniques to minimize stress on the knee joint.

- Warm-up and Stretching: A thorough warm-up routine before physical activity can help prepare the muscles and ligaments for exercise, reducing the risk of injury. Incorporating dynamic stretching exercises specific to the activity can further improve flexibility and mobility.

- Use of Protective Equipment: Wearing appropriate protective gear, such as knee braces or supportive footwear, may help reduce the risk of ACL injuries, especially during high-impact sports.

- Rest and Recovery: Adequate rest between workouts or training sessions is crucial to prevent overuse injuries and allow the body time to recover.

If you suspect an ACL injury or have concerns about knee health, consult with our sports medicine surgeons for personalized care and guidance.

Stay informed about upcoming webinars and events, and gain valuable insights on leading a healthy, pain-free life from our experts by subscribing to our monthly newsletter. Click the button below to join!